Your life/death is a feature series sharing stories and insights from people whose lives have been shaped by death.

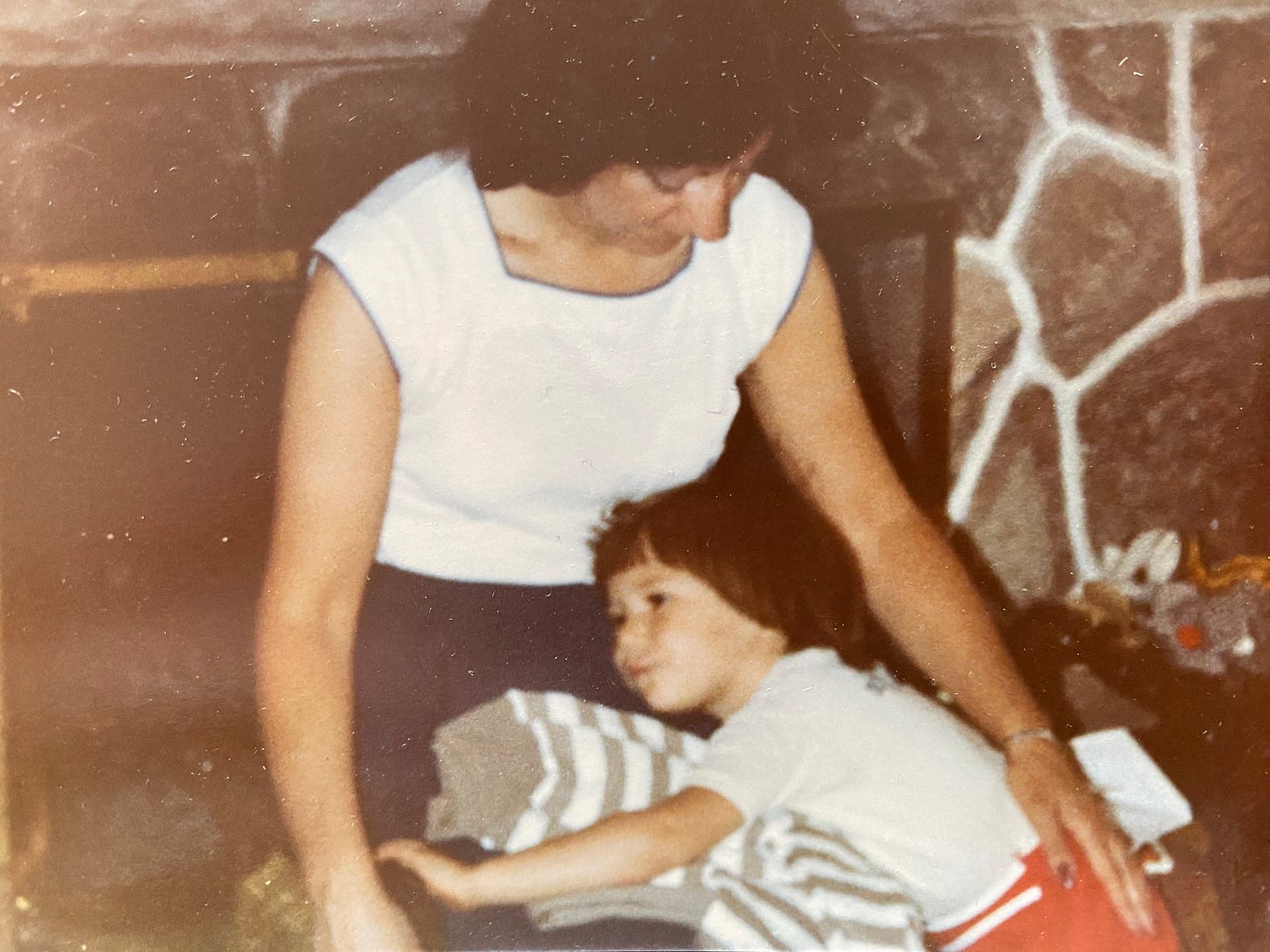

My mom was tough. Italian Taurus tough. She ran her household, her schedule, her life to her liking, and no one and nothing was going to throw her off her routines.

That was until the cancer she’d been fighting off for 20 years returned and made it clear that it was, in fact, in control. And until it decided when it was going to take her, someone else had to take control: of her household, her schedule, her life. That someone was me. It was a very unfamiliar position to be in, making every decision from what we’d eat for dinner each night (if she was up for eating at all) to scheduling her appointments (and taking her to each and every one).

Suddenly, life as both of us knew it was over. I packed up my apartment and moved in with her, and we both hung on tight through the roller-coaster of end-of-life cancer care, where just when you think you’ve settled into a routine, another change forces you to reorient yourself and establish a new one, which you get used to just in time for something to change again.

Which is one of the reasons why it’s easy to get so focused on all of the responsibilities of caregiving and lose sight of the fact that your mother is dying and what you’d like most (and probably what you both need) is to just curl up next to her, hold her hand, stroke her hair, and tell her how much you love her. But for many of the times you could have — should have — done that, you instead notice that her prescriptions are getting low and you run off to the drugstore to refill them, or you spend hours on the phone arranging nursing and PSW care, and almost forget that this is your mom who very soon you aren’t going to have around at all.

It’s hard to say what turns you into a caregiver robot. Maybe some people find it easier to balance the practical with the emotional. For me, it was easiest — though if I’m honest it wasn’t really a choice, more of a default setting — to just shut down emotionally and power through the day with purpose and intention, knowing that the tasks I was knocking off the list were making her more comfortable. But whether by choice or default or circumstance, at the end of the day settling into robot mode made me an efficient caregiver, but not a connected one, and I missed some opportunities to be in tune with what my Mom and I needed emotionally, and to embrace and fully live our final months and days as mother and daughter. I was Mom now, and there was no going back.

We had moments that poked holes in my armour — giggling together at the oncologist’s office for reasons I now can’t recall, sharing a small glass of wine leftover from cooking — but I was often focused on practical matters, and so left a lot of words unsaid, questions unasked, kisses and hugs undelivered.

I think of the note I received from a friend just minutes after my mother died, which included the advice that I tell her how much I’m going to miss her, how much I don’t want her to go. By then it was too late to say that, or anything, to my mom. And at the time I panicked, thinking I had failed yet again and desperately wishing I could turn back the clock even a few hours.

But as the years since her death have passed, I’ve tried to remember the moments where I expressed those sentiments to her through things I did rather than words I said. When I’d go to Loblaws and take a spin through the Joe Fresh racks to find leggings and tunic tops that would be comfortable for going to appointments but also keep her looking and feeling put-together (which in all her years was very, very important to her); or when I sat on her bed and we scrolled through a “what was everyone wearing” photo gallery of Prince William and Kate’s royal wedding and we gave attendees the full Joan Rivers Fashion Police treatment. (Kate’s dress got all the thumbs up from both of us, in case you’re wondering.)

And with even more distance, I’ve also learned to show myself the grace to accept that taking care of all the practical matters that were of utmost importance to her day-to-day comfort was itself a love language, even if they weren’t always accompanied by soothing words or a gentle touch.

I used to look at the caregiving phase as a time when my life was “on hold” because my existence was made up of two things: my job, and caring for my mother. I thought that I’d hit the un-pause button and my life would resume its forward motion with dates and movies and vacations, just as before. It was after she died that I realized how wrong I was. That life is made up of a series of phases from birth until death, that no state is permanent, and that caring for her was itself a phase that both of us were passing through that was just as rich and lovely and painful and complicated as any other. I didn’t have to “wait” for my life to restart after she died. This was life, and if I didn’t embrace it as it was, I would miss not only its painful challenges but also its potential for wonder and humour and intimacy.

Because time can feel like it has slowed down in this phase, and as the hustle and bustle of social commitments and adventures falls away, there’s more space to find quiet moments of connection. And in fact, they are quite easy to find. Often you just have to ask yourself, “what do I need right now?” Or, “what does mom need?” Often the answer is found in those giggles and glasses of wine. And you’ll find yourself savouring each and every one long after the moments, and your mom, are gone.

By Andrea Janus